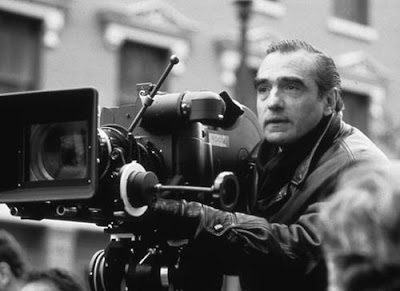

More than just a movie-maker, Martin Scorsese is the self-appointed guardian of American cinema history. Since the early 1980s he campaigned for more durable color film stock, and the preservation and archiving of old American films, while promoting the cinema of the past to modern audiences. For Scorsese, the cinema of the present is always and necessarily influenced by the past. Scorsese is also the 'critical' King of Hollywood. Whether juggling big budgets and mainstream connections with large studios (Universal, Warner Brothers), delivering star vehicle and box-office successes (The Color of Money, Cape Fear, The Departed, Shutter Island), or indulging in more personal projects (The Last Temptation of Christ, Kundun, Hugo), Scorsese has retained his reputation as the quintessential auteur.

An independently minded cinephile, Scorsese's relationship to popular cinema has been an extremely productive one. While best known for savage but complex exploration of masculinity and violence in films such as the New York based Mean Streets and Taxi Driver, the searing biographical boxing picture Raging Bull or the epic gangster narrative GoodFellas, Casino, Scorsese's output has been extremely varied. In his period adaptation of an Edith Wharton's novel, The Age of Innocence, Scorsese's attention to rituals of self-contained societies takes on a new dimension.

The surreal 'King of Comedy', the yuppie nightmare movie After Hours, or the contemporary women's picture Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, all testify both to the diversity of Scorsese's career and to the range of influences.

Basic Theme : Religion

Religion remains a consistent theme: almost all of Scorsese's primary male characters voice a fascination with religion in some form. Mean Streets' Charlie (Harvey Keitel) is fixated with the idea of his own spiritual purpose. The archetypal selective devotee, his desire to do penance is at odds with his actions. Taxi Driver's Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) believes himself to be acting out God's rage against the lowlife of New York city; Cape Fear's Max Cady (De Niro) is similarly obsessive; while Raging Bull's Jake La Motta (De Niro) punishes his body both in training and in the boxing ring in an attempt to atone for his sins.

In retrospect, the earlier films seem to be leading towards Last Temptation's explicit wrestling with Christianity. Attracting intense reactions from some religious groups, the film, has Christ appear to leave the cross and experience marries life with Mary Magdalene. Scorsese argued that it was his intention to show Christ as a real man rather than as a faultless spiritual being. Thus, Christ's (William Dafoe) inner emotional struggle and the consistently female image of sin converge.

Scorsese stated in interviews that: "Jesus has to put up with everything we go through, all the doubts and fear and anger..........he has to deal with all this double, triple guilt on the cross. That's the way I directed it, and that's what I wanted, because my own religious feeling are the same." The Last Temptation of Christ can be interpreted in two distinct ways; either it posts Christ as human being, or it raises Scorsese's vision of masculine identity to am omnipotent spiritual level.

Basic Theme : Masculinity

Notions of masculinity, a sense of community and the influence of religion on personal identity are all themes common to Scorsese films. In fact, Last Temptation suggests and attempt to universalize masculine experience by having these themes transported from the usual urban, late-twentieth century setting to biblical times. Though Scorsese cannot be simply cast as a misogynist, his personal perspective and belief systems are unashamedly patriarchal, grounded in Catholicism. Women feature mainly on a symbolic level, serving as projections of male spiritual conflicts (even, it might be argued, in The Age of Innocence)

Alongside the romance of the gangster and of the male ritual that is so much in evidence in Scorsese's work, characters like Travis, Charlie, Jake LaMotta and Cady can all be understood in terms of a journey towards salvation through self-knowledge. Such themes chime with the contention of the critics, that an auteur film is dominated by the search for self-awareness.

Attitude Towards Violence

An early Collaboration with Paul Schrader produced one of Scorsese's most controversial works. A story of 'God's Lonely Man', Taxi Driver follows insomniac Vietnam veteran, Travis Bickle, as he dreams of ridding New York of the 'scum and filth' that populate its streets. The film builds slowly towards a violent climax, wherein Travis, a confused vigilante, acts out his fantasies. While the absence of satisfactory narrative conclusion works against either character motivation or salvation, it is this inconsistency of structure and theme that attracted such strong reactions from audiences and critics alike.

Scorsese's films certainly have an ambiguous attitude to violence, since the audience is invited to gain a perverse pleasure from witnessing acts of brutality. In this sense, Scorsese's vision is less about the search for salvation in self-knowledge, and more about the glorification of man's inherent potential for violence -- hence the struggling nostalgia for a masculine community of action in GoodFellas in which Tommy (Joe Pesci) functions as a perverse kind of hero. Although these patterns may have as much to do with the repeated presence of actors like De Niro, Pesci and Keitel, this quality of 'New York-ness' has delivered a traceable identity of urban, working class, male communities in Scorsese's work.

'New Hollywood' Film-maker

Scorsese concentrated mainly on making his name as an independent film-maker. Of course, this begs the question what is meant by independent film-maker? In the context of American cinema of the last fifty years, two distinct versions offer themselves: on the one hand, those working in commercial film-making outside the auspices of the major studios (loosely be termed the field of exploitation), and on the other hand, those working in a festival-fueled circuit of independent film-making (a sort of art cinema). Scorsese is an independent in both senses: One of his first features as director, Boxcar Bertha, was produced by 'King of the B's' Roger Corman.

Scorsese's early successes (independent and mainstream) began in the early 1970s when his contemporaries were such film-makers as Coppola, George Lucas, Robert Altman, Brian De Palma and Steven Spielberg. Part of both a nascent art cinema and what came to be the 'New Hollywood', the success of Scorsese's career has been his ability to operate across both spheres -- independent and mainstream, innovative and conservative.

Together these film-makers represented a new generation who took a full advantage of the more experimental space that an industry in desperate search of an audience permitted. Scorsese has certainly exploited his reputation and star presence (characterized by an enthusiastic cinephilia), both in relation to his own projects and while serving as producer/ executive producer for others.

Significant Collaborations

Scorsese's career has been marked by important collaborative relationships. Thelma Schoonmaker first worked with Scorsese as editor on the 1969 "Who's that Knocking at my Door", and has edited all his films since 'Raging Bull' to Hugo (she received Oscar for Raging Bull, Aviator and The Departed). Cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, has been one of the regular since After Hours. Writer Paul Schrader is one of Scorsese's best known collaborators, although he has only worked on three films, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and The Last Temptation of Christ. Robert De Niro (seven films) and Leonardo DiCaprio (five films) has starred in more Scorsese films than anyone else, having a significant input into the films (Harvey Keitel is also a Scorsese regular).

The Savior

Scorsese does not attempt to hide the collaborative nature of his work, promoting it as an extension of his love of cinema history against the unthinking cult of the director. He will a cinematographer because of a particular style from the classical era he wishes to reproduce, or new techniques he wishes to learn. In the last decade, Scorsese has taken on the role of elder statesman in the movie industry. He has tirelessly campaigned for many movies' re-release and critical recognition, as part of an ongoing project to restore neglected films and film-makers to present-day audiences. Scorsese has emerged as a liberal defender of the movies as art.

He has the critical credibility of independent film-maker, combined with the box-office draw of a major Hollywood player. His intentions, focused entirely on saving the soul of cinema, makes him a 'Savior' and true 'Guardian of Cinema.'

Websites:

Book:

Scorsese By Roger Ebert

3 comments:

Well, what can I see? It's as meticulously done as ever!

It's very hard to do justice to cinema titan like Scorcese in writing, but you have done it. DeNiro performance in Raging Bull has to be one of the finest performance ever by an actor. It's good that Scorcese is continuing to make films still so that the new generation will explore his old films as well. I took my brother reluctantly to The Departed and he became a huge fan of Scorcese.

@Murtaza Ali, Thanks for the comment.

@Sandeep, Thanks for the comment. Scorsese is not only making good films, but he has also become a versatile kind of director, who could handle any theme.

Post a Comment